It’s not easy to remember all the names of those who have impacted American history. Most of us know a few vice presidents who made their marks because of the way they came into office: Andrew Johnson, Theodore Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson all became presidents because of an assassination. Harry Truman took over for FDR when he passed away.

But looking at a couple of men who played second fiddle in the executive branch of the government can be interesting. They served in administrations early in the 20th Century. They weren’t from the same party, but they did balance their parties’ tickets. And they were both from Indiana.

Charles W. Fairbanks (1852-1918) and Thomas R. Marshall (1854-1925) are the two.

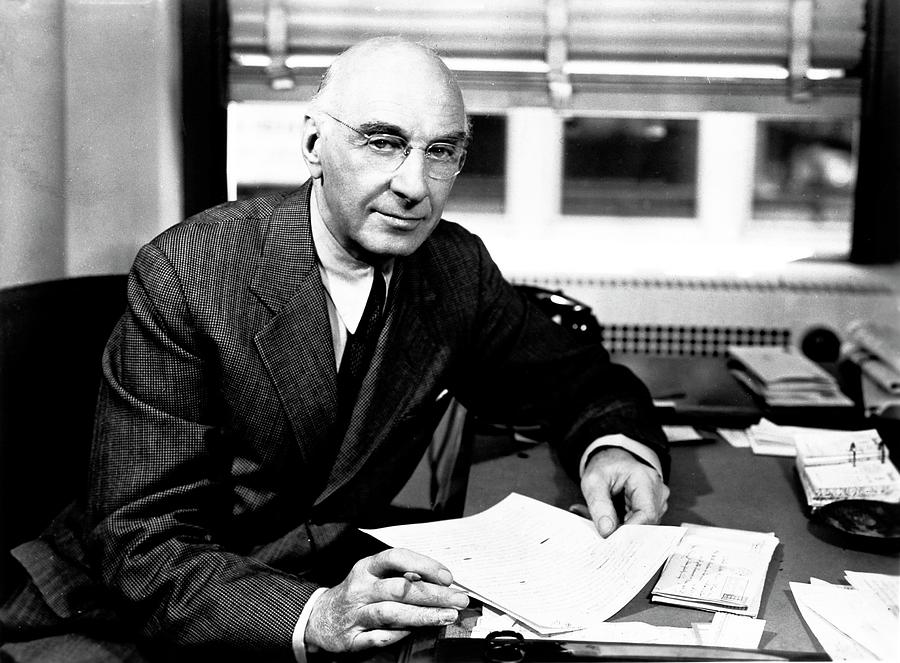

Fairbanks (indyencyclopedia.org)

Marshall (britannica.com/biography)

For the better part of four years, Theodore Roosevelt (“that —— cowboy!”) didn’t have a vice president. He believed he didn’t need one, a view much different than when he was in the office. Indeed, the “steamroller in trousers” had an extraordinary first term without a v.p.

In the next election, Indiana Senator Charles Fairbanks appeared on the Republican ticket with Roosevelt to please party conservatives. A native of Ohio, Fairbanks practiced law in Indianapolis for many years with cases involving the railroad industry. He had a major interest in the Indianapolis News. In 1904 the “hot tamale” (Roosevelt) and the “Indiana icicle” (Fairbanks) won the election in a landslide.

During the second Roosevelt term, Fairbanks wasn’t invited to cabinet meetings or consulted on decisions. He did preside over the Senate during the Pure Food and Drug Act hearings, which passed to benefit all Americans.

Republican William Howard Taft, chosen by his friend Roosevelt with James S. Sherman of New York as his vice president, won in 1908. Sherman died of Bright’s Disease just before the next election. Taft went on to serve in his preferred office, chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

(quotefancy.com)

Democrat Woodrow Wilson chose Thomas Marshall to run with him in 1912. Marshall, governor of Indiana, was known as “a liberal with the brakes on.” The election followed an uproar for the Republicans whose party bosses nominated Taft again. Theodore Roosevelt formed the new Progressive (“Bull Moose”) Party, splitting the voting public. Wilson won, Roosevelt came in second and Taft, third.

Like Fairbanks, Marshall did not attend cabinet meetings. This practice carried over to Wilson’s second term as he was in Europe for World War 1 peace talks. After the president had a stroke, Marshall was kept in the dark about his condition, which left Mrs. Wilson to make decisions for the country according to her husband’s wishes.

Marshall is known for his dry humor. While presiding over a debate about what the country needed, he said aside to a colleague, “What America needs is a good five-cent cigar.” He also stated once, “I was the Wilson administration’s spare tire – to be used only in case of emergency.” And when he left office, he quipped, “I don’t want to work. I don’t propose to work. I wouldn’t mind being vice president again.” At home he headed back to practicing law and writing books, including his autobiography.

By the time Marshall retired, Fairbanks was dead. He had been the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1916 with Charles Evans Hughes, but they narrowly lost. He is known for the skill he demonstrated in the Foreign Relations Committee of the Senate, as evidenced by the city in Alaska which is named for him.

Leaving the topic, I will again quote Marshall: “Once there were two brothers. One ran away to sea; the other was elected vice president. And nothing was ever heard of either of them again.”

Maybe these two weren’t as inconsequential as it seems. Each helped his partner get elected, changing the course of the story of America.

Sources: pbs.org, in.gov, theodorerooseveltcenter.org, millercenter.org, and James H. Madison: Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2014. If you’d like to read an excellent history of our state, start with this one.